- Home

- Olga Chaplin

The Man From Talalaivka Page 4

The Man From Talalaivka Read online

Page 4

“Horko! Horko!” his friends called out, signalling to him and his new bride. Peter grinned and, taking the cue, took Evdokia’s hand, eyes flirting as they danced to a Ukrainian wedding song. He caught her eyes, shining, teasing him, as they moved in step in their traditional dance.

“Come on, Petro!” his friend Mikhaelo teased, challenging him. “Let’s see which of us is leader in the kopak!” His brothers pulled him away from his bride. The party circled them as they dared each other, and competed in their agility and sport to the ever-faster pace of the music. In these unguarded moments that seemed to have been snatched from his early freer days of the past, he threw himself into the energetic excitement of the dance. Not for a long time in these recent years had he felt such a sense of freedom and elation. For those few enraptured minutes he let go of the responsibilities and concerns he had been wearing for so long. The grape wine and samohon, the music and reverie of the bridal party, did its work on his senses: spurred him, artist and athlete as one, to leap ever higher, to the party’s cheers. Proud, exhilarated, his inhibition abandoned, he felt himself soar like a free bird, high above the mundane, to some higher plane: it was intoxicating, liberating to his senses. Evdokia watched, entranced, her heart daring to raise hopes for their happy union.

At celebration’s end, Evdokia embraced Yakim and Klavdina and honoured Stasyia and the priest, through tears of joy and sadness, and looked back one last time to the ‘collective’ farmhouse that had been her temporary home. “Don’t worry, Dyna,” Peter gently anticipated her emotions. “From now, our home will be your home … let’s make our way home.”

It was still light. He followed her, observing her careful steps as she lifted her long skirt and embroidered white linen underskirt, and as she sat composed, waiting in the buggy. “I hope I can live up to her ideals,” the thought flickered in his mind as he checked his horse and tied her bag securely at the back. The circumstances in which he married his first wife, the beloved Hanya, had been auspicious, even relatively easy, under Lenin’s more relaxed leadership of the twenties. The circumstances under which he was now to provide a home for Evdokia and Vanya were vastly changed. There was little hope his father’s farm would remain their home for long. And food was becoming more and more scarce by the week.

The cold night air, as he steered his horse in the direction of Kylapchin and his family’s farm, brought a chilling reminder of what lay ahead of them. He hoped fervently he would be able to keep the promise he made, before the priest and before his God, that he would keep his young wife safe, for all time. He held fast to the horse’s reins, held fast to the hope that their farmhouse had not yet been taken or, worse still, set upon by the local soviet-led bandits roaming their countryside in this totalitarian nightmare. Vanya waited for his new mother; Evdokia waited for her new home. He waited for a future, which was still unknown.

His horse manoeuvred the last south-westerly turn towards the farm. They were still a few kilometres away, but already he could see the red-black blaze of a huge fire in the direction of their farm. He caught his breath in disbelief. It could not be possible, surely, for fortune and misfortune to go so closely hand-in-hand for him in a single day.

He cracked the reins, unable to think beyond saving his family’s farm, unable to think of his own safety should the soviet soldiers try to stop him. The pain, anxiety and adrenalin that had been held down all these past days and months, in a finely balanced scale of emotions, suddenly shot uncontrollably in an opposite direction, throwing his fears to the fore. Juxtaposed balance of emotions was gone, logic escaped. In its place was the agony of not knowing whether he could save his family’s farm in time. Worse still was the agony of not knowing whether Vanya had come to harm. He cracked his horse’s reins again, racing almost recklessly towards the billowing red-black inferno in the night sky, towards he knew not what: towards the man-made hell.

Chapter 8

What is it that makes a man risk everything he has, to achieve what is almost an impossible goal? Peter could not bring himself to answer this as he took the stained envelope proffered by his new assistant and pushed the letter deep into his coat pocket. He pretended composure, aware of the increased political intrigues surrounding him, and nodded thanks to his watchful colleague.

“Dakyuy, Dimitri … it is from my dear elders …” He caught the assistant’s arched brow. “He knows its contents, even before I do!” he realised, dismayed. “Another ambitious young man being groomed for higher office!” He feigned distraction and quickly collected the papers for his kolkhoz duties. He needed to remove himself from this cauldron of stultifying suspicion; to read his Yosep and Palasha’s censored words away from prying eyes.

His horse grazed on autumnal grasses as he leaned against a denuded tree, its yellowed leaves crumpling about him. He looked towards his next kolkhoz of duty from his resting place on the bluff-like hill. An uncompromisingly chilly wind whipped up, flattening the dying grasses and forewarning him of the barren landscape that would soon descend upon them, and trap them in its deep snows.

His fingers, blackened from the censor’s ink that besmirched the victims’ words, trembled as he tried to decipher the contents of his elders’ letter. Too many months had passed with the censor’s tampering. He could not gauge, from this last letter, whether or not his parents were still alive. His shoulders and body stiffened, like a visceral shell holding in his anxieties, his fears for his parents.

He looked out to the kolkhoz of his next calling, but hesitated. He felt the letter and sensed its fragility, felt also the depth of the blackened words denied to his Yosep and Palasha. He pondered the situation, weighed up the risks. He mentally laid out his life before him.

His beautiful first wife and baby son had died at the start of the famine that felled his fellow Ukrainians. But he had quickly remarried, primarily to give a home and mother for his surviving three-year-old son, Vanya. He could even hope for a happy and lasting marriage with Evdokia, this young woman who was attractive, agreeable and stable, even if she wasn’t his first great love, Hanya. Yet he was prepared to risk it all for this secret, reckless, almost suicidal plan to see his parents, who were now eking out a wretched existence in Siberia, until who knew when.

He knew the risks. He was acutely aware of the politics in his region of Sumskaya Oblast, in this north-eastern part of Ukraine, so close to Russia’s borders. This was no longer Lenin’s Russia of the early 1920s. It was Stalin’s Russia. The first Five Year Plan was executed with ruthless effectiveness, soon to be declared a ‘total success’ by the Communist regime. Collectivisation was almost complete, certainly in the Ukraine. His parents had been labelled ‘kulaks’ or wealthy farmers and were imprisoned in 1930, their farm confiscated. Their family, like so many of their Ukrainian fellowmen, was herded off to kolkhozes in this so-called ‘agrarian revolution’.

His parents, elderly and in poor health, were spared execution. They were given the mandatory sentence of five years in a Siberian labour camp and were languishing in prison when he remarried. It seemed even now almost a surreal situation to him: happiness at finding another life partner, and relief at saving his little son from illness and likely death; and despair at being powerless to help his parents. “God, keep them safe,” he prayed daily, willing them to find strength to live.

Now, a year later, as he looked eastward to the distant horizon in the direction of the Siberian wastelands, he was making the decision to try to see his parents, to take some hidden food to them, to comfort them if he could. The risks were enormous. He would be missing from his work as a veterinary practitioner in the local kolkhozes. His travel papers would be forgeries of the proper documents allowing travel through and from his region. He held his breath as he considered the dangers. Travel in the Ukraine was hazardous enough at the best of times. But under Stalin, with Communist dogma and implementation of further restrictions, it was foolhardy. The famine was worsening by the week, and month. Life was becoming cheap and dispensabl

e. Peter knew this and observed, with increasing anguish in his travels for work, the daily hardships endured in his own Oblast.

But he knew, only too well, that if life was precarious in his own region, it was nigh almost impossible in the Siberian wastelands, hastily created camps to isolate huge numbers of Ukrainians and other nationalities for political expedience. He wanted to reach his incarcerated parents before it was too late. “And Halka must be struggling … she is still so young!” It was a further pressing reason to get to them. His youngest sister, only fifteen at the time his Yosep and Palasha were sentenced, chose to go with them to the labour camp. Her reasons were noble: to care for her parents, regardless of the consequences. She could not bear to see them go and to never know their fate and condition in the camp. Practically, there was little opposition to this from the regime: one less mouth to consider, one less body to accommodate in the kolkhozes; and the relatives were also relieved not to be labelled as housing the daughter of sentenced persons.

It was already late autumn, 1931. He had anxiously observed the prematurely denuded trees in his own Sumskaya Oblast as he strove to meet the kolkhozes’ deadlines in his increased rounds of veterinary work. He had heard that winter had also come early to the Siberian camps. This last letter, trembling in his fingers, only confirmed those other sporadic ones, and again was too censored to make any sense of his parents’ condition. He sighed, his heart heavy. It had taken so long for this last letter to reach him that he feared his parents might already have met their doomed fate. If he was to try and see them, it had to be before winter was fully upon them, before travel in Russia and in Siberia was made impossible by the harshness of the climate, the massive snows, the freezing temperatures.

For Peter, though he didn’t know it at the time, it was the defining moment of his life.

Chapter 9

Timing was everything. If he had seen a complete map of the Soviet Union, if he had really known the distance he was planning to cover, it must have been only cursorily considered. Just as his parents must have experienced weeks of transportation to their Siberian wasteland prison, so Peter also expected a long journey. ‘Revolutionary’ changes had altered his beautiful Ukrainian culture and life to a point where it was now unrecognisable. But some things always stayed the same. Travel within the regions, and throughout the whole of the Soviet Union was always counted in days, weeks, months. This secret journey would be similar to any that a State official would make for his Party.

Luck would also have to play a part, in order for him to succeed in his plan. His years as veterinary practitioner in his district, and now in the kolkhozes he was forced to supervise, made him relatively valuable to the Communist regime. The regime had brutalised the farmers and peasants, taking all their possessions, and burnt farms to force the villagers into kolkhozes. The hapless farmers took revenge and killed their own livestock rather than lose it to the Stalinist regime.

Peter’s work, in saving what livestock he could, temporarily gave him a higher status in the political upheaval. “It must count for something,” he thought as he considered the possible routes he would need to take, “that already I am trusted on longer journeys without checks, at times.” He had to use this to full advantage in the limited time available. The irony, that he was placed in this situation in his work, whilst his parents suffered at the hands of these same officials, played on his mind. It deepened his resolve to help his parents, to save them if it was possible.

Luck of a different kind, in the form of his despairing close friend, gave Peter the chance to finalise his plan. “Count me in with you, Petro! We will need each other for this journey, my friend!” Mikhaelo pleaded with him, in the secrecy of their meeting. His parents also had been sentenced, but recently, to the same area of Siberia. Each knew the risks involved if their plan was discovered. Trust in each other was paramount, on pain of death.

Their plan was simple, audacious. A senior veterinary practitioner, with an assistant, travelling on official business across the Oblasts, seemed plausible. Only the Oblasts were covered in the documents. Their real destinations were omitted: Omsk and Novosibirsk, the new cities created by the regime and from which the Siberian wastelands and labour camps stretched northwards towards the Arctic Circle. Communist Party propaganda, zealously printed in the Party run newspaper Pravda, espoused the virtues of the gold mines, oil research and industrial expansion of the Siberian region. But others knew the truth. Peter’s, and Mikhailo’s, parents were evidence of this.

In final preparation, they meticulously wrapped salted pork in thick durable cloth, which they then sewed into the front lining of their long, heavy winter coats, still serviceable from their army days. The weight was staggering, yet light compared with the inner burdens they carried. This hidden food was for their parents. It was too dangerous to visibly carry food anywhere now. Not only was food scarce. The regime was following a campaign of starvation in the Ukraine and elsewhere. People were killed in acts of desperation for carrying even small parcels of food, and they knew this. What little money they had was for emergencies, should their forged food vouchers fail.

In the murky dawn light, Evdokia saw her husband to the door of the kolkhoz farmhouse, which they shared with four other families. Peter seemed his usual, sprightly confident self. He resisted holding her that moment longer as he departed, her soft blonde hair merging with hoary mist as she turned to close the door. She had no inkling of what lay ahead for them both—he had spared her this, as the secrecy protected not only her and little Vanya, but also the other families in the farmhouse. The regime was superb at reprisals. It was best that she knew only that he had extended travel for official business. “Dear God, be near to them,” he pleaded as he turned to grasp his horse’s reins.

If there was a moment of truth to be faced at their parting that chilly morning, he pushed it even further from his mind. His new wife and little son needed him. Yet he needed to make this mad, possibly last, gesture to his parents, who may already have perished in Stalin’s labour camp.

Chapter 10

Pretence and opportunity were the daily dice Peter tossed and rolled as he played Russian roulette with their lives, picking their way north-eastward through the Oblasts. It was a haphazard and indirect route, yet believable. It reflected the idiosyncrasies of the regime’s own bureaucrats following inexplicable instructions in the blaze of the first Five Year Plan. And his years of national service and subsequent travels beyond his own Sumskaya Oblast prepared him to act ‘nationally’ on this journey. He was the confident senior veterinary practitioner, with an assistant, on an important mission around the countryside. His veterinary’s satchel, with its distinctive insignia on the front, became the immediate foil to anticipated questions from police and officials. The battered bag metamorphosed into a symbol of honour in the urgent need to save livestock at this crucial stage of collectivisation. Using clichés and correct terminology, he was a convincing, loyal bureaucrat. “God help us, if they see the discrepancies,” he warned himself. He flicked again through the forged documents and checked the locked clasp.

He knew he had to be courageous, for both of them. Watchful of Mikhaelo’s trembling state as they approached each searchpoint, he showed his daring and wore the mantle of senior bureaucrat ever more confidently, having encouraged Mikhaelo to act obsequiously as his junior. As each part of their jigsaw journey took them closer to their crossroads destination, Peter’s shoulders tensed taut like steel. He felt with each passing day, and each checkpoint, as if he were in some kind of circus, walking the tightrope, jumping the hoops to the crack of an invisible master’s whip. Reality became almost blurred in the daily charade: the caged creature and its master pitted against each other, in a ruthless contest of wills. It was a wicked reality, and one that could end their lives.

At last, in wan light, Ekaterinburg came into sight. “Ah! We may yet have a chance!” he whispered in relief and gently nudged Mikhaelo. The first part of their journey in their pil

grimage to the labour camp was complete. From this Ural Mountains crossroad, the great Trans-Siberian Railway turned its back on European Russia and looked eastwards to the Siberian and Asian Oblasts. Soft snow was falling; winter was not far from this distant doorstep of the Arctic Circle. Peter and Mikhaelo instinctively drew closer to each other for solace and support. Food was already scarce, and they hadn’t yet begun the Siberian part of their journey. They counted their kopeks carefully for their meagre meal. They huddled in the carriage, and soaked crusts of stale black rye bread in a soup caricatured as Russian borshch. They ate silently, thoughtfully. They were still eating. They dared not dwell on whether their parents were.

Each kilometre that the ancient carriage of the Trans-Siberian Railway gained on the snow-covered tracks to the Siberian outposts gave Peter hope that they might yet reach their destination, and achieve their goal. His calculation that fewer police and officials checked these trains heading in the opposite direction to civilisation was proved right. Omsk was in darkness as the train waited, seemingly endlessly, for orders to continue, but he guessed, rightly, the reason for the delay. “So this is what it is like to be the ‘soldier labourers’ for Stalin’s new Bolshevism!” his mind registered. The grey shapeless forms of prisoners being herded slowly to their graveyard destination outside Omsk were just visible. It was a chilling sight.

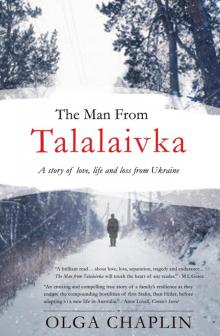

The Man From Talalaivka

The Man From Talalaivka