- Home

- Olga Chaplin

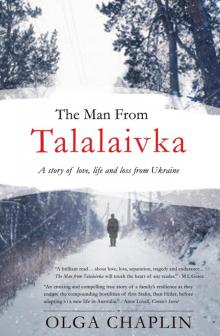

The Man From Talalaivka

The Man From Talalaivka Read online

The Man from Talalaivka

The Man from Talalaivka

A story of love, life and loss from Ukraine

OLGA CHAPLIN

First published in 2017 by Green Olive Press

Green Olive Press

5 Lindsay Street

Brighton VIC 3186

www.greenolivepress.com

Copyright © Olga Chaplin 2017

Olga Chaplin asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any other information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Creator: Chaplin, Olga, 1944- author.

Title: The man from Talalaivka:

a story of love, life and loss from

Ukraine / Olga Chaplin.

ISBN: 9780992486068 (paperback)

Subjects: Immigrants--Australia--Fiction.

World War, 1939-1945--Conscript labor--Germany--Fiction.

Ukraine--History--1921-1944--Fiction.

Ukraine--History--Famine, 1932-1933--Fiction.

Ukraine--History--German occupation, 1941-1944--Fiction.

Dewey Number: A823.4

Cover and internal design: Gloria Tsang/Green Olive Press

Printed in Australia by Griffin Press

For Peter and Evdokia

Ditte moyi ditte, ditte moyi kvitte

Children my children, children my flowers

Taras Shevchenko

Note on the text

Occasionally throughout this work of historical fiction, I have taken the liberty to present key words and phrases in a personalised version of Ukrainian, as there were regional dialectical differences during the era. I have tried, as authentically as possible, to capture the language my parents used while at the same time acknowledging that my translations may not be entirely accurate and hope the reader will forgive me any errors.

PART I

Chapter 1

December 1929

A massive poster caught Peter’s eye as he entered. He paused, surprised. Lenin’s simple but inspiring portrait was gone. In its place, Stalin’s pseudo-benevolent face stared back at him, raised arm pointing the way forward to this, his first Five Year Plan. Peter looked about him and shook his head; sensed that though it seemed but a small change, it was significant.

Talalaivka’s central office was bristling with electrifying tension. Comrade Stalin’s protégé, Kaganovich, had just made his personal appearance, leaving extraordinary orders from the Secretary General. They would need extra forces from their military police and army units in order for this final radicalisation of agriculture to succeed at this breakneck speed. The consequences, the soviet officials knew, would be horrific. Already hardened since Stalin’s rise to power, and tense with anticipation, they braced themselves for the onslaught of human misery that the implementation of these extreme orders would cause.

The tension stung Peter’s face more than the biting air as he strode through the great door. He hurriedly took off his heavy cap, brushed its snow against his long army coat. He was anxious to return home, to sanity, to Hanya and his infant sons. He headed towards the back office to speak to Constantin, his senior veterinary colleague. His work papers were yet to be completed, then signed by soviet officials, before he could take his leave. Already he was several days late returning from his circuit of veterinary duties. And the winter snows had not yet set in.

He looked again at the poster and shook his head thoughtfully. At that moment a senior official, observing him, tapped his shoulder in recognition.

“Drastysa, Petro Yosepovich!” Peter returned the obligatory soldier’s salute. These days, it was difficult to separate the civilian from the military, or from the police. He knew he was walking a fine line of tolerance from the extremists among them.

“Ah, Petro,” Constantin smiled, his face lighting up. “I’m glad you’ve returned safely. Such heavy snows.” He grasped Peter’s shoulder reassuringly and glanced to the outside office, with its prickling atmosphere. “And so dangerous now.” He stopped, as a soviet official passed. Peter nodded. He could not comment. His ailing colleague had little to lose now, whereas he had his young family to consider. His fingers itched to complete his quota forms, his heart impatient to return to Hanya and their little sons. Vanya would delight in the few sweets he had wrapped, and even in these several weeks baby Mischa must have grown from his tiny proportions. This year’s Saint Nikolas’s feast day will be especially poignant, he promised himself, in spite of the political difficulties and economic hardships.

His horse, ploughing soft snow almost effortlessly as they headed homeward, seemed to sense his urgency. Peter’s spirits lifted. He felt revitalised in the freshness around him. Virgin snowflakes, carried by swirls of light morning breeze, danced about him like miniature white doves freed in flight. Each kilometre distanced him from the hotbed of political turmoil and conspiracy that had overtaken the Talalaivka bureau recently. He turned his back, temporarily, on the chaos the triumvirate had brought, with General Secretary Stalin at its helm.

In these few short years, since completing his army service and training, Peter saw changes within his Ukraine that could only be explained in the light of Lenin’s untimely death, and the ensuing power struggle between members of the Bolshevik Party’s Politburo. Whatever ephemeral unity the Party apparatchiks published in Pravda, Peter and his trusted friends knew differently. Now, with Lenin’s new economic policies abandoned, ostensibly for the ‘purity’ of Bolshevik ideals, and Stalin’s power supreme with the implementation of this first Five Year Plan, all certainty was gone. No-one in this part of the countryside, in Sumskaya Oblast, knew from where their daily bread would come, nor under which roof they would be protected. And already, the gulag labour camps were swelling at an alarming pace. Such was the legacy of Stalin and his henchmen’s application of the so-called ‘purist’ Bolshevik ideals.

He reined his horse at the southern crossroads of Talalaivka, and headed south-eastward towards Kylapchin and his family’s farm. He paused, allowing a unit of soviet militia, led by trained soldiers, to pass. The captain eyed Peter, recognised him in his heavy army coat, and tipped his cap in soldierly fashion. Peter responded. He had trained with this man who, like him, was energetic, keen to do well. Peter had chosen the civil service once his official national training was completed; the captain had remained in the army. “A good leader,” Peter noted thoughtfully as the unit passed, “but for whom, now that our circumstances are changing so rapidly?”

He cupped his hand over his eyes, protecting them from the sheen of the snow. Still so many kilometres to make good, but a perfect day nonetheless. The anticipation of being with Hanya and the infants spurred him on. He smiled as he thought of these irreplaceable jewels that filled his heart. Sweethearts, and so young, it seemed, he and Hanya had married immediately upon his discharge from the army; had planned and built their tiny xatka on his father’s lands at a little distance from the family’s farmhouse and had seen the birth, first of Vanya, several years ago and now of their baby, Mischa.

If ever there was a time of bittersweet contemplation, Peter felt it was now. The sweetness of his idyllic marriage, and his healthy infants. The bitterness of the fast-changing political and social events, and the consequent economic difficulties already ravaging the countryside. He instinctively reached down to check the sacks of food scraps fastened carefully to the saddle: like an expert scavenger, he had picked out still-fresh cabbage and beetroot, even black rye bread, carelessly discarded by the Talalaivka officials, whose daily

supplies were purloined from the local area. “Such good fortune for my family,” he reflected, “we may not need to struggle. But what of the others, who don’t find enough food?”

At last, his xatka’s chimney smoke welcomed him. He reined his horse under the cover of the sloping roof and sprinted the last paces, threw open the door, the sweet smell of his home surprising his nostrils anew. He hugged his Hanya and touched her soft pale face, her silky dark hair, and felt the closeness of Vanya in his arms. Baby Mischa looked strong, content, and indeed had grown. Peter breathed relief. He knew he would need to hide this additional food; he determined to reinforce their secret cellar to keep it safe through the winter. But for now life was as good, as complete, as any honourable Ukrainian man could wish for. “Give us strength,” he prayed silently to his magnanimous Maker, “that we won’t be hounded into kolkhozes … that we won’t be starved out of our own farmhouses.” He looked forward to the feast of Saint Nikolas’s celebrations. Hanya and little Vanya had already chosen their small fir tree, and were collecting acorns and fir cones for its decoration; the few kukurhyske, baked and carefully hidden, to be brought out on the eve of the festivities.

He could anticipate the celebration of Saint Nikolas: the tradition and joy that a child’s symbolic birth almost two millennia earlier had instilled in his Ukrainian culture. But he could not have known that already, in Moscow, an opposing celebration was about to take place for the tyrant Stalin, who would eclipse these long held genteel traditions and eventually destroy them. Shafting home blame for his own economic mismanagement to the people who could least resist, Stalin would seal the fate of any burgeoning liberal ideals that had begun to bloom under Lenin. Peter could not know it then, that twisted power and malice would savage and overpower the inherent good that had been the mark of his Ukrainian countrymen. It was a brutal irony that the ageold tradition celebrating birth and life would be obliterated by Stalin’s orchestrated birthday celebration, honouring his power, destruction and wasteful death of innocents.

Peter could not have known that it would be his family’s last Christmas celebration together. His heart, for the moment, was spared that pain.

Chapter 2

A long line of soviet militia specked the snow’s horizon, making their way to Yakemovitch village from the Talalaivka road. Evdokia craned at the window, imbued with her childhood habit of sighting her father’s buggy on the crest of the hill near their farmhouse as it returned from the village. The heavy-coated militia soldiers were too indistinct, but they aroused her curiosity, their horses mushing slowly along a ridge before, serpent-like, slithering over it, they disappeared from view. These militia soldiers could not be connected to the Yakemovitch village meeting, she was certain: her father and brothers would be returning any moment.

She smiled, in anticipation of the good news the soviet officials had promised them. At last, the villagers would put behind them the hardships they had endured this past year; the debacle of all their spring-sowing wheat and most of their winter food that had been taken from them was the result, the local officials insisted, of misunderstandings around implementing Stalin’s new quota orders. She did not understand the political machinations taking place around them, but trusted her father’s optimism that, despite the moderate Bukharin and his supporters having recently been removed from the Politburo, Stalin and his bureaucracy would make good their pledge to improve their lives.

She gazed at the wondrous vista before her and marvelled, child-like, at its beauty. Saint Nikolas’s feast day was not far hence and, as of old, her family would now be able to savour the celebration of Christ’s birth. Her eyes feasted on the sun’s ephemeral rays as they sparked the tips of soaring trees, turning them into spires of the village churches now extinct. The warming rays brushed transiently at the shadows of white-bearded oaks and firs that lined the nearby hills. Though her body was not yet satiated with the promised food, her heart swelled in anticipated gladness. From this day, nature’s generosity of beauty would be equalled by the fairness of Stalin’s regime.

She rushed to the door as her father’s buggy appeared on the hillside and ran bare-footed to the great barn nearby to push open its heavy door for her father’s horse. The light borshch broth simmering on their ancient earthen stove would warm them, and her mother need no longer fret at the dwindling meagre supplies. Almost childishly, she licked her lips to taste an imagined sweetness, wishing to return to the days when her father, cautious in every way, would bring a few kopeks’ worth of halva and honey for the family.

“Ny, Yakim …” Klavdina gently ventured, noting uncertainty in her husband’s demeanour. “How went it today? When will they bring back our wheat?”

“Ah, the meeting …” Yakim hesitated, distracting himself with his soaked hat, laying it carefully at table’s edge, trying to compose himself. He sat down slowly, heavily, touched his greying beard as if deep in thought, and bowed his head. Suddenly, his shoulders shuddered. He groaned, as if in pain. Evdokia, shocked, stood by helplessly. She had never witnessed her father in such a distressed state.

“They tricked us!” His eyes could not look at his family. “We came willingly, peacefully … They told us, beforehand … we would have our grain back … they would find ways to improve our living. But instead …” He faltered as he shook his head in disbelief. “We are to lose everything! They are forcing us into a kolkhoz! They won’t even tell us where … but it will be soon!”

Panic pierced Evdokia. She could not fully comprehend the import of the village meeting, but her intuitive sense told her her family’s future was changed from that moment. She could only watch, confused, as Klavdina comforted Yakim and grasped his proud shoulder.

“Yakim,” Klavdina reassured him, searching for words, her inner strength surpassing her diminutive body. “Our farm, our inheritance … What good will our farm be, if any of us should come to harm? At least they haven’t labelled us kulaks, as some unfortunates have been. We will have a home to go to … We will be given food … Our family will be safe …”

“I won’t need to go to a kolkhoz!” Procip, Evdokia’s twin, announced in manly fashion. “They are giving us young men a choice: the kolkhoz or the Donbas mines. Perhaps even a Tractor Machine Station, some day!” Procip looked at the youngest, not yet fifteen. “Makar! Once I’m settled, you can join me! We should even earn enough to send some kopeks back to Mamo and Tato!”

A sudden commotion outside distracted them. Procip, closest to the door, cautiously opened it. Evdokia turned from her distressed parents and watched in amazement as a young captain, in full army uniform stepped in, followed by a dozen soviet militia soldiers.

“Yakim Kyzmayovich Shcherbak,” he spoke quietly, respectfully, tipping his cap. “I have orders to deliver this document to you. You and your family are to accompany me, immediately, to a nearby kolkhoz … it will be decided later where your family will be permanently placed.” The captain’s modern regalia gave his status: he had his early training in Lenin’s new army, was disciplined, efficient, not threatening.

Yakim took the document, glanced at it and placed it on the table without perusing it. The captain watched quietly, gave Yakim a few moments; then stepped closer to him, dropped his voice. “Yakim Kyzmayovich … please … I would encourage you to obey these orders. Your family—all your family—will remain safe, if you follow them. Come now …” His voice dropped to a whisper, “I can’t speak for what may happen if you don’t. You are safe with me; my men will obey my orders; they will not hurt you or your kin. I will see that you arrive safely at the kolkhoz. Other soldiers may become reckless with you …” His young man’s eyes pleaded with Yakim to listen.

Yakim shook his head, defeated, then nodded agreement. The order of eviction lay on the table, unread. He motioned to his family to gather their belongings. Evdokia looked out through the open door. The remaining soviet soldiers were stationed at the barn. She hurriedly bundled her clothing, her heart paining as she folded her embroi

dered long petticoat shirt that had been denied its nuptials blessings so long ago. The waiting cart, soldiers at the fore, would only allow perenas and some utensils. Already the militia were circling the farmhouse, coveting possessions. They would return in due course, to take as they chose under Stalin’s new erratic orders, once the small farmholder and his family were removed.

The sun had passed its peak. The shadows drifted along the hillside as the captain, at the head of the posse, gave his order to move. The cart jerked, the gentle snow deceiving in its transparency, gradually camouflaging the family farmhouse until it had become one with the growing shadows of the hilly snows.

Evdokia could not know, as the blurred outline of their farmhouse disappeared like a mirage in the powdery mist around her, that she would never again step on that soft Ukrainian snow nor the soil of her family’s farm; would never again be permitted to re-visit the family place which had given her so much security and strength and love. Now, this long line of black-coated militia soldiers was taking them to a place unknown. The militia line had turned into a malevolent serpent, doing the bidding of the cowardly Stalin, taking them ever closer to ultimate disaster.

Chapter 3

“Hanya, moya Hanya,” Peter moaned as he knelt on his knee in homage as his hand gently caressed the hardening clumps of clay: yearning, reaching to Hanya, to Mischa. Time stood still as he grappled with the suffering. He was almost oblivious of the sounds around him as life continued inexorably in nature’s purposefulness, obeying a higher command. But all was stillness, below.

His hand searched helplessly across the mound. So small a plot for wife and infant son; so short, so precious the time together, now separated indefinitely. Already wild grasses were claiming possession, the sweetness of the flowers at grave’s head crushed by nature’s willful servants. He rested his head on the wilting blooms and closed his eyes, blanking out the cold reality as he drew in the last of their youthful scents.

The Man From Talalaivka

The Man From Talalaivka