- Home

- Olga Chaplin

The Man From Talalaivka Page 3

The Man From Talalaivka Read online

Page 3

Peter responded in the affirmative, taking his place beside his elders, and nodded respectfully to the hosts. His quick eye observed Evdokia in the half-shadows. At that moment sunlight from a nearby window shafted across, flickered at her head. “My God,” he thought, taken off-guard, “her hair is so blonde.” His own beloved Hanya was dark-haired. Until that moment he had not considered how different this young woman, Evdokia, might be. He realised the enormity of responsibilities on him that would emanate from this crucial meeting. He could not let his family down. He had to impress the host family, be a credible suitor. But he also had a higher responsibility: to be honest, to be true to himself, to not deceive this woman, Evdokia.

With the blessing of the victuals complete, Peter took the initiative. The grape wine chaffed at his throat; the borshch-like broth was delicate in taste but sparse. But he knew their difficulties, and generously thanked the hosts for their gifts of hospitality. His praise was exaggerated, but it pleased them. They warmed to this attractive young man who, despite suffering widowhood so recently, remained well-mannered and understood the value of conviviality.

Evdokia listened quietly, intrigued. The voice was warm, expressive. She had only briefly glimpsed him as he entered the great room. Now he aroused her curiosity. She eased her stiff posture. She had no preconceptions, but had not expected a potential suitor to be articulate, intelligent, entertaining. Stasyia sensed the moment. “Peta, I am told your family’s orchards are among the best in these parts,” she smiled, tilting her head as she half-winked at him. “The orchard here is in such disrepair now … but still, some fine specimens remain—before the soviet officials turn even those into another wasteland! Evdokia,” she nodded encouragement, “perhaps you could show Petro the remaining orchard … some of the fruits might yet be saved, with his knowledge.”

Evdokia blushed, and complied politely. Sunlight dazzled her as she stepped into the courtyard. Her heart skipped a beat as she saw him clearly for the first time, in radiant daylight. He was taller, more handsome than she had expected, unlike anyone she had previously met. He had an exuberance that surprised her. “Will he find me exciting enough?” she could not stop her inner voice asking. Her own life with her parents and siblings had been so ordered, even controlled. She held her breath, unable to gauge the situation, and could only smile at his gallantry as he held back heavy branches as she passed along the pathway amongst the gnarled old orchard trees.

The last of the trees’ blossoms fused with a honeyed scent as Evdokia passed him. The scents evoked tender memories Peter had kept hidden these past painful months. Now, he observed Evdokia in a different light, watched as she walked elegantly before him. He realised there was much to discover in her. He had to dissociate himself from his early love; to not compare her with Hanya. “How is it that she is still unmarried?” he wondered to himself. He determined to ask her mentor, when next they talked privately.

Stasyia could hear their voices, and laughter, as she strolled towards them along the unkempt path. She smiled to herself, relieved. This meeting seemed to be developing well. She returned to the farmhouse, to the burdens of the families: the uncertainties of daily life, of survival under collectivisation and Stalin’s rule.

Suddenly, a voice called out from the courtyard. Peter stopped, puzzled by its urgency. His brother Fedir ran to the orchard, panting. “Petro!” he burst out, almost exploding with agitation; then, seeing Evdokia, stopped for a moment and excused himself as he caught his breath, his face red with perspiration.

“Petro,” he gasped, his voice strained. “We must return to the farmhouse this minute! The soviet dogs are after our elders. They’ve come to question them … to interrogate them. Some idiot told them our parents are in hiding from the authorities! The fools! They’re threatening us with a warrant for their arrest! They wouldn’t listen to Ivan’s explanation—they’re holding him as a surety. They say if our parents don’t return now, then ‘he will do’ as the eldest son—the bastards! I’ve given them my word I would return with them immediately. We must move quickly, Petro … before those madmen torch our farmhouse!”

Peter looked at Fedir, who was usually so steady but was now almost wild-eyed, agitated. He shook his head, more to himself than to Evdokia, and pursed his lips, his face intent. He said nothing. But he knew this was the moment he had been dreading these past months, now that the farm was in full summer production, ripe for the taking. Somewhere in his psyche the absurd reached out to him: ‘Pospile,’ their precious family name: ‘ripe’ in name, ripe for the pickings by these lazy Stalinist cronies.

He beckoned Fedir to fetch his parents and turned quickly to ready the buggy for their journey back to Kylapchin. Preoccupied, he barely remembered the formalities of departure, could not be certain if he acknowledged Evdokia as she stood silently nearby, watching, confused.

Evdokia stood stiffly beside Stasyia watching as the buggy, driving speedily behind Fedir’s fast horse, receded through the haze of sunlight and churning dust in the direction of Kylapchin. She could not be certain if he had looked one last time to the farmhouse and their hosts. She watched them disappear along the narrow countryside road, and stood passively for a time to regain her composure. She could not explain her feelings of abandonment, even though this was an extraordinary misfortune for Peter and his family. She was too inexperienced in matters of the heart to know whether or not she had made an impression on Peter; too afraid to think of the consequences of being rejected by this attractive, lively man. She could only contain these doubts, these uncertainties, deep within her, and hide her disappointment yet again.

“Boje,” she prayed silently, “bring some good from this meeting.” Fate had already dealt her a double blow: it had first worked inadvertently against her through her older sister Hannah’s grief at losing her fiancé in the Great War, refusing to marry another suitor; dealing her a second blow, later, when her own young suitor could wait no longer. She closed her eyes and pictured Peter, capturing their moments in the orchard. She at least could say to her heart that, for a fleeting time, one perfect summer afternoon, she briefly played with love, almost lost her heart again. That was the legacy Fate left her, this time.

Now, Fate snatched her chance of finding happiness again in love. If she never saw this appealing widower again, she would always remember his liveliness, his winning smile, his hazel eyes communicating with the world. That would be her reward for being tricked yet again by Fate.

Chapter 6

Jugular veins visibly pumping, rifle strap held tense at the shoulder of his ill-fitting uniform, the soviet guard eyed Peter coldly as he unlocked the dilapidated cell door. He stood at its opening, legs stiffly astride, finger twitching at rifle’s trigger-lock. “A few minutes only!” His edgy voice punched at the stale basement air.

“He’s even younger than my brother Hresha,” Peter gauged silently, watchfully. He sensed the guard’s nervous disposition; he had been witness to such breaking-point tension during his own army experience. This young militia recruit to Stalin’s massive police bureaucracy was unpredictable, could not be trusted with his deadly weapon.

“Harasho, dakyuy,” Peter nodded respect for the man and his rifle. It was too risky to ask for more time. He guessed, accurately, the reason for this young guard’s edginess. Upstairs he and his comrades were massively outnumbered in the packed oppressive hall of this outpost prison of Romny by anxious men and women clutching visit permits. Peter could still smell the acrid adrenalin of the crowd’s collective anxiety. The silent swarming mob could easily overwhelm the few guards. Only their fears for their imprisoned relatives kept them in check. There were no guarantees they would set eyes on their loved ones, no guarantees their relatives were still alive. In this tense, almost surreal atmosphere, and now alone in the basement, the guard’s rifle had become his ultimate authority.

“Batko … Mamo,” Peter called out into the vaporous semi-dark. He sensed his elders’ presence, their discomfort in the dan

kness as his eyes searched out their silhouettes. Yosep clasped his son’s arms, held tight his strong shoulders, as if for a moment of reassurance. Peter felt a surge of relief rushing through him. His parents were still safe, for now. He kissed his mother’s uplifted cheeks, felt her thinness as he embraced her.

“They give us so little time here … on purpose,” he warned, softly. He searched deep into his jacket pockets. “I’ve brought a little sustenance … God willing, I’ll be back in a day or two with more.” He brought out the cloth-wrapped parcels of black rye bread and kobasa, and hid them quickly beneath the thin perena Palasha had been grudgingly permitted to bring.

“Batko,” he lowered his voice, trying to remain calm, “what is your situation now? Ivan told me they were interrogating you. We all know they can only be trumped-up reasons. You have done everything they wanted—met their quotas. It must be the farm they’re after!” He straightened, his tone determined. “I intend to speak to the officials here … plead your case, to get you released. They know they are getting all the produce they can, with us working the farm to the maximum!”

Yosep gently pressed his outstretched hand on his son’s chest, in an affectionate gesture to quiet him. “Petro … it is no use.” He hesitated and, glancing warily at the guard, dropped his voice to a whisper. “It is too late. They have sentenced us … The NKVD dogs! They’ve deputised NKVD men as judges for this so-called court. There is no trial here … No appeal … Just the sentence.”

He drew back for a moment as he collected himself. “They’ve sentenced us to five years … five years, in a hard labour camp in Siberia! They call us ‘kulaks’! We are but proud Ukrainian farmers! We’ve rarely crossed the threshold of a kulak’s door in all the years of toiling our own land!” He nodded his head, knowingly. “We understand the reason. A convenience to remove us from the farm. They will send us as far from our Sumskaya Oblast as their cattle trains will go … to a hell-hole that none of us have ever heard of!” He paused and smiled wryly into the dimness, despite himself. “What good will our old bones be in that Siberian permafrost? There are already enough Ukrainian souls there, to fertilise their icy forests!”

Peter’s stomach suddenly wrenched. He felt a clamminess, a sickening wave of nausea running through him. Instinctively he turned to one side, trying to contain a need to vomit, the shock hitting him hard. He felt as if someone had punched the very life out of him. Sweat pricked painfully at his forehead, at his body. He leaned against the damp cell wall, his eyes trying to focus on his brave parents; breathed deeply, slowly, willing himself to remain collected. More than at any other time, his parents needed his support, his clear thinking.

He knew what this meant. For Yosep and Palasha, it was a sentence to a prolonged death.

The guard shuffled his boots, edging to his final command for Peter to leave. “Dobreye cholovik,” Peter appeased the shifty militia soldier. “Give me one more minute … please … to farewell my close ones.”

He turned to his parents, standing forlorn in their crushed garb, yet somehow dignified in this dank cell. “Peta …” his father beseeched him. “Don’t burden your heart any more, son. We will live as we must, as long as God wills us. Peta, we want you to look ahead … to your happiness … Protect Vanya… Do what you must, son. You need to take a wife, be a family once more. It will ease our hearts, to know you and Vanya are not suffering.”

Peter nodded in acceptance, moist eyes concealed in the dimness. His parents, always so fair and selfless were now, in the midst of their own suffering, giving him their blessing to seek his own peace. He yearned to comfort them. But he knew he could do no more.

“I understand,” he whispered, almost to himself, “what has to be, so it will be.”

He felt their tears as they embraced him one last time. The guard’s impatient boots crunched the worn stone floor, rifle butt scraping his heavy uniform buckle. Peter looked back one last time, his parents’ visages motionless in the dusky light. He would plead for his parents, whatever the risk. The NKVD men might yet be swayed by his usefulness to this new Stalinist regime, by his experience as veterinary practitioner. He had heard of reprieves, of some softening in sentences for inexplicable reasons.

But, deep within, cold reasoning told him it would be futile. His parents were not Bolshevik Party members. They were of no consequence to Stalin or his cohorts of the new dogma. If anything, this new so-called troika regime gained perverse pleasure and thrived on stripping them from their farm, from their Oblast, from their Ukrainian heritage. Little wonder the very word ‘kulak’ had become an infamous instrument of propaganda for Stalin and his bureaucracy who, like a pack of howling wolves, tore increasingly faster through their prey, leaving misery and death in their wake. Peter knew his parents’ fate was sealed. He had yet to see what his would ultimately be.

Chapter 7

Stasyia lovingly adjusted the long, embroidered cloth framing the miniature icon of holy Mother and Child and passed her eye over the makeshift altar. It was devoid of its ecclesiastic artefacts, but the simple roses and cornflowers at table’s end exuded a tranquil beauty as they picked up the sun’s rays from the nearby window. She took a deep breath of satisfaction. “Praise be to our Lord,” she murmured. She was pleased her part in this union, despite almost overwhelming difficulties, had been received so well. “Give us all strength to live good and long lives,” she prayed silently to her Maker. Every moment was precious, in these uncertain times. Crossing herself, she bowed low before the altar table and kissed its fine linen cloth as if the icon of the Lord were still in its honoured place; then, straightening and smiling warmly to the wedding party, she motioned them to the hallowed setting. “Drastysa, Petro, i dorohi; drastysa, Evdokia, i dorohi,” she welcomed them, and awaited Father Chernyiuk as he blessed the families in the ‘collective’ farmhouse. She fondly observed him, pleased with his neat appearance. His shabby black cassock had withstood her careful handling in the cold spring water and even evinced a new respectability before this scented altar.

Peter stood taller, more confident, head held proudly high before the priest. He glanced quickly at Evdokia, smiled at her pensive face. “So calm,” he thought, “… so far away.” She seemed removed, almost unattainable, her emotions hidden beneath her short lace veil. He breathed in her honeyed scent complementing the delicate perfume of flowers woven in her braided hair. The wafts of summer’s blooms mingled with the reassuring hint of incense as the priest took out his precious gold-embroidered ecclesiastical ribbon and kissed it, as the nuptials began.

Peter drew a deep breath, turning his mind from the painful events of the past months and of his last visit to his imprisoned parents. This was a time for living, for new commitment, for some joy. There could be no more room in his mind for doubts or regrets; no more room in his heart for sorrow, for what could have been. Only room for a future, for healing, for affection and love to grow.

As Stasyia gently bound their hands with the fine gold ribbon in the symbolic joining of two souls in marriage, Evdokia could feel Peter’s pulsating warmth envelop her. She tilted her head slightly and smiled gently beneath her veil, her seeming remoteness broken. They moved in unison, slowly, Ivan and Fedir’s unadorned crowns of wildflowers held high above them, and Father Chernyiuk guiding them in their first steps as man and wife.

Stasyia carefully unpinned the square of lace shielding Evdokia’s face. They crossed themselves and kissed the priest’s upheld cross. “Go forward, good man and wife,” he beseeched them. “Keep to each other in this life. Live your lives according to our Lord’s ideals.” He crossed himself and held up his cross in a final blessing for the attendants to acknowledge, then carefully folded his gold ribbon and hid his precious relics deep in his cassock.

“Well, now,” he smiled, old eyes brightening, “let us have our celebratory drink, share our meal and be glad for this day!” His eyes rested on Peter. “Let us also pray for our loved ones who cannot share this day with us. Pray for the

ir safety … for their good health. We must be strong for them.”

As their wedding dinner progressed, Hresha stepped forward and embraced his older brother. “Oi, Petro!” he called out, teasingly. “Look what I’ve brought for the celebration! This’ll keep us on our toes, once the grape wine runs out and the samohon is on the table!” He held up Peter’s old balalaika. Peter grinned and eyed him mock-threateningly, but pleased nonetheless with the promise of frivolity. It was time for celebration, not for mourning or despair. There had been enough time for those in the past; there would be time enough, again, for that in the future. Today was for living, for savouring the good moments.

He looked affectionately at Evdokia as she blushed politely and received congratulatory embraces and jovial comments from his brothers. His heart filled with pride at her composure, her courteous manner and warm response to his family who, until now, knew her so briefly. “I am truly fortunate,” he thought to himself. He realised there were no guarantees in this life but he intuitively sensed Evdokia would have in her the qualities, the strength of character, that would sustain them in the life they would share from this day. He sighed to himself. He desperately needed time to be alone with his new wife. He looked ahead to them sharing quiet moments, and to adjusting to each other’s ways. “And Vanya will be glad to be with her,” he surmised thoughtfully. “She takes her duties seriously … he will find in her a warm and caring mother.”

The simple feast-meal and grape wine raised their spirits. For so short a time, Stalinist dogma and bureaucracy were forgotten, soviet officialdom pushed aside. The samohon, clandestinely reclaimed from a hidden cellar, and the beckoning balalaika, made the men game: brought on their songs, their dancing. The ‘collective’ farmhouse families joined the wedding party. Someone brought out the pipe-flute, another expertly pumped a hand accordion. “Veprahaete xloptsi koni, a na zavtra pochevate …” the men began a spirited folk song, a reminder of their past unfettered lives, the music and laughter reverberating in the lofty ceiling of the farmhouse.

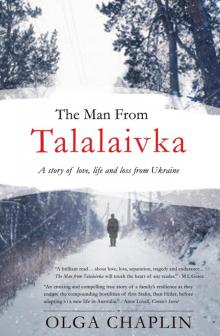

The Man From Talalaivka

The Man From Talalaivka